All these particulars and no lens to focus them. One has the same feeling at the annual neuroscience meetings. “We are surrounded - nay crushed - by a mass of details demanding explanation.” “There are now before us many more questions than there were earlier,” he said. And yet, as his biographer notes, “the opposite proved true.” As his lab expanded, with more scientists, dogs and experiments, Pavlov was cursed by a proliferation of variables. “The time will come - and it will be such a wonderful moment - when everything becomes clear,” he wrote in a moment of anticipation. Like Anna O., he was caught between two impulses - excitation from the circle and inhibition from the ellipse. Originally calm by nature, he began yelping and running in circles, habitually barking for no apparent reason and drooling copiously. As the ellipses were made increasingly rounder and less oval-like, the task grew harder until finally Vampire could not tell the two shapes apart.Īnd so the poor dog snapped. One shape would be reinforced, the other suppressed. The animal had been trained, through salivation experiments, to react differently to two images: an ellipse and a circle. Pavlov thought he recognized a similar phenomenon in a dog named Vampire. The result of these opposing psychological forces, as Freud saw it, was a nervous breakdown. She was devastated by his plummeting health yet determined to repress her grief and maintain a cheerful face.

Freud believed that Anna’s condition - hysteria, it was called back then - arose from the stress of caring for her dying father. That is how poorly the man has been understood.Īfter reading about the case of Anna O., made famous by Sigmund Freud, Pavlov began contemplating neurosis in a dog. “Are they not the last links in an almost endless chain of adaptabilities which appear everywhere in living creatures?” We expect this kind of grand philosophical pronouncement more from a William James than from an Ivan Pavlov. “The movement of plants toward the light and the seeking of truth through a mathematical analysis - are these not phenomena belonging to the same order?” he wondered. By weaving together webs of these connections, he hoped to capture the ineffable. Stimulus-response, stimulus-response, stimulus-response. But for all the important details that are emerging, we are still just poking at the surface of the phenomenon that most fascinates us: the mind driving the curiosity that gives rise to science, art, literature, music, the highest human endeavors.įor Pavlov, the pieces - the atoms - were the simplest measurable associations. Gathering last month for the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, researchers reported their readings from microelectrodes, PET scans and optogenetic sensors - instruments that have far surpassed the precision of Pavlov’s tools. The Brain Initiative was preceded, in the 1990s, by the Decade of the Brain, which was followed (as if the easier problems had been solved) by the Decade of the Mind.

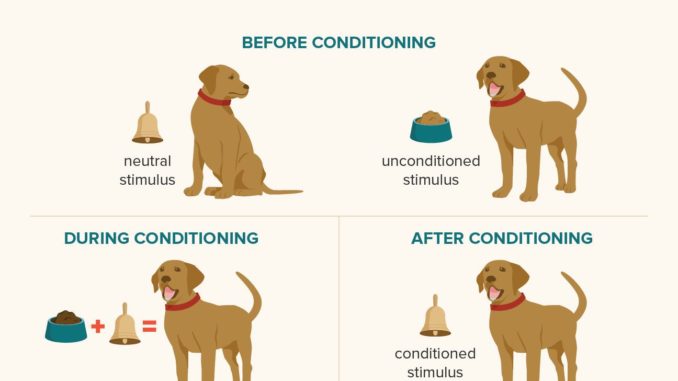

Todes’s book, I kept wondering how much we have really accomplished since Pavlov’s time. Our brains have been conditioned with the myth. Yet when we hear his name, we reflexively think of a drooling dog and a clanging bell. That was also Pavlov’s goal: to build a science that would “brightly illuminate our mysterious nature” and “our consciousness and its torments.” He spoke those words 111 years ago and spent his life pursuing his goal. Todes, a medical historian, describes a man whose laboratory in pre-Soviet Russia was like an early-20th-century version of the White House Brain Initiative, with its aim “to revolutionize our understanding of the human mind.” In an excellent new biography, “ Ivan Pavlov: A Russian Life in Science,” Daniel P. This is not the Pavlov most people think they know.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)